William Gibson vs. David Lynch

Two Remarkable Visionary Creators Compared and Contrasted

For a brief time in my young life, David Lynch held sway. In 1990, a girl was found dead, wrapped in plastic and the whole small town of Twin Peaks was shattered and slowly exposed over the course of two television seasons. Those two seasons straddled a war that, at least for me, drew a deep line of demarcation, a before and after.

David Lynch’s works are often drenched in 50’-feel and small-town nostalgia on the surface. Underneath is the sordid truth of human frailty and weakness, vice and crime. Often, woven through, is Lynch’s own beliefs—transcendental meditation—”experiencing the treasure within”—, reincarnation, some sort of belief in achieving enlightenment and immortality. His stories can be in turns soap opera-ish, slapstick comedy, and psychological horror, deep-seated evil with a twist of surrealistic disconnect. For David, the movie is the thing; like Flannery O’Connor, he detests efforts to get behind the story to a hidden meaning.

“A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is.”—Flannery O’Connor

I think David would agree with that. He is, as a modern film and television maker, a singular generator of “what did that really mean?”, yet is as deaf as FBI Deputy Director Gordon Cole to his fans in this regard.

David Lynch’s works are not something I can wholesale recommend; many of his topics, when depicted on film, are disturbing. Bob, in Twin Peaks, is an entity which inhabits people and does gross and base evil, driving a father to repeatedly rape his own daughter and ultimately, to kill her and her doppleganger cousin. Women are trafficked across the border at a bordello, a tiny waitress is constantly dominated and battered by her long-haul trucker/drugrunner-dealer husband. She retaliates by having a fling with a local badboy high school football jock. Cocaine fuels the evil; the Evil has always lived in the woods. This is just Twin Peaks. Made for tv, it’s not as graphic. Long shots of various people screaming disturbed me more than any visualized crime—perhaps because of the implied spiritual dimension.

David’s nostalgia in the first two seasons of the show are replaced in the third season, aired much later, 25 years to be exact, with a loud message. You can’t go back, people change, evil has replaced goodness as the surface of things, in the ascendency. Gone is the beauty of the old town, the mysterious forest with it’s secrets, the Bunk House Boys as eternal watchmen.

This is the rise of the ugly strip mall and the death of the mysterious and ethereal. A zeroing out of the scale. One fan analysis thought that, in the end these characters disappeared in the last episode because, of course, they never were real, but only a means to express ideas that, as David Lynch often likes to say, “are like fish that you pull out, one after another”.

David’s world of Twin Peaks is rooted in 1950’s small-town life. Jocks in lettermen’s jackets swagger around and act tough, a moody, handsome loner on a ‘75 Harley Electra Glide. screams Brando-knockoff, and the lumber mill and logging are the ancient economic heart of the town. But modernity is getting its nose under the tent. Bobby Briggs rolls out in a ‘69 Plymouth Barricuda in the pilot, but has a newer Pontiac Firebird Trans Am throughout the first two seasons. The economic planners of the town are moving from timber to to tourism and the magnates of the two businesses are in literal bed with one another. Drugs and under-age prostitution and murder have come to tear the bucolic heart from this small town and drag its corpse into modernity in season three, aired in 2017 on Showtime.

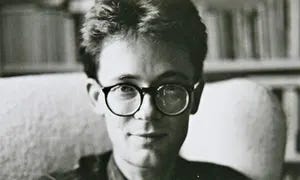

William Gibson, mid-1980s

William Gibson is an author, principally. He is known for his forward-thinking writing. He is considered the godfather of cyberpunk. The terminology that we use every day when talking about technology touches on Gibsonian terms—cyberspace, coined in the 1960s, was brought to popular use through his books. And many tropes of The Matrix are gifts Gibson gave such as the idea of Matrix as a digitized place one may experience and interface with others far or near—”distance” and “here” become meaningless in the Matrix; and “jacking in” and downloading data to oneself, “I know kung-fu,” Neo says from his seat next to Dozer. He imagined the impact of a worldwide internet when it was still ARPANET, available only to academics. He looked at body modifications for both fashion and for augmentation when paired with technologies. Neuralink, anyone? I wonder if Elon ever read Gibson.

Gibson’s playground was the near future in his first six or so books. He doesn’t look back with nostalgia, there is no sense of wistfulness. When his writing does take a breath to look back, between the first three books and second three, what comes out of his ink well? Steampunk, of course. The Difference Engine was co-authored with Bruce Sterling. He can’t even look backwards without also looking sideways. I won’t hold it against him, if I did I’d be the fool.

Themes emerge. In the first three books AI, virtual reality and augmented reality become the main tools to tell stories populated by irredeemable characters of ambiguous morality. They live in a gritty, noir world of unrepentant capitalism at its worst and lowest. International corporations operate as sovereign nations. This, I believe, is where Gibson shows his chronological place in time. Born in1948, much of the books and movies popular in his young life would have been detective stories and film noir. He seems to have acquired the taste and it’s a good fit to his world of despair, moral ambiguity, and bald use of power and violence for personal gain at any cost.

His second set of three novels focuses more on the cult of personality prevalent in mass media. Ours are still flesh and blood aren’t they? But Gibson imagines ones tailor-made, engineered for our consumption and irresistible, through which people en masse are controlled and sedated. I guess it’s a TV party tonight!

Gibson’s third set of three can’t run fast enough, or perhaps he can’t as time is catching up with him in one respect—setting. And so these three are contemporary in time. His writing is sharp enough to land all three on the bestsellers’ list. I’d love to have legs that tired.

These two men have similarities, more than I realized when I first began thinking about the two men. They were born two years apart, both in small and rural places. Lynch was born in Missoula, Montana in 1946. The population then was about 20,000 and it was a logging town. Gibson was born in 1948 in Conway, South Carolina, population around 5,800. They likewise moved around often, as his father’s job demanded. William’s father died when he was just into grade school in Norfolk, VA. , so he and his mother moved back to Wytheville, Virginia, where she was from. It was of similar size, about 5,500, in coal country. While young William Gibson was doing a slow burn in Wytheville, the Lynch family chased the father around—Sandpoint, ID., Spokane, WA., Durham, NC., Boise, ID., and Alexandria, VA.. By the time the Lynch family hit Virginia he must have been in his teens; as an Eagle Scout, he was at the inauguration of John F. Kennedy. His father’s job as USDA research scientist, augmented by his mother’s work as an English language tutor, meant that he was raised in the dream of white picket fences and upper middle class affluence. Three hundred miles to the southwest in Wytheville, 70 short miles from Beckley, WVA., thirteen year old William Gibson was living a life much closer to the bone; he was a gangly, tall boy in a small town who didn’t like sports, had rejected religion, and would rather sequester himself with books. By thirteen he knew he wanted to write. His mother did have or find the means to send him to a boys’ boarding school in Arizona where he at least learned to be a little more social. His SAT scores in English were nearly perfect: 148 out of a possible 150. His math scores were nearly inverted, 5 out of 150.

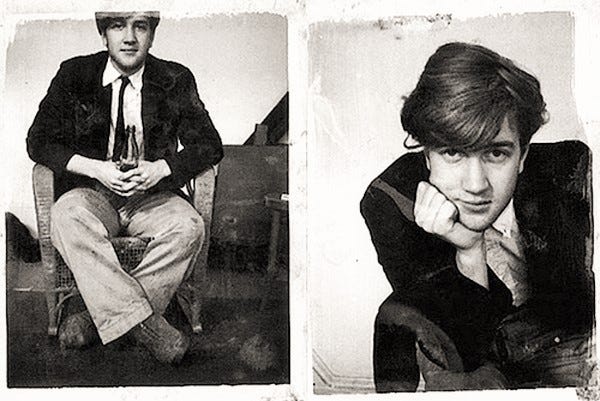

David Lynch, 1969

Meanwhile, affable and outgoing David had finished high school and gone on to art school in D.C. for a year, then transferred to another art school in Boston, where he roomed with future front man of the J. Geils’ Band, Peter Wolf, as freshman. That didn’t last, and David decided to kick it in Europe with a buddy and paint under the tutelage of Austrian impressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka. Oskar wasn’t available, and the planned two year bohemian adventure lasted two weeks. I remember crossing an anecdote that it was because David went through the money so quickly that they didn’t stay, but I haven’t found the source on that yet.

Meanwhile, the Lynch family had moved yet again, this time to Walnut Creek, CA., about 20 miles east of Oakland in the Bay area. Oddly, being around the Bay in the 1960s didn’t interest David. Had that been William, he would have been happy to deep-dive into the counter-culture and do all the substances and hippy chicks he could.

A few years later he did. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

So David went to Philly and roomed with a buddy, enrolling in the same art school he was attending. By ‘67 he had got his girlfriend pregnant and married her. They bought a house in the hood.

William’s mother died in 1966. He dropped out of school and spent time in Cali and Europe. After his draft board hearing (more like an interview) in 1967 he boarded a bus for Toronto to chase hippy skirts and the devil’s lettuce. The draft board never did get back to him.

He spent the rest of the 1960s living in the counter-cultural milieu of Toronto. Along the way he collected a wife and a high-school diploma. Mr. and Mrs. Gibson sent a few years of the early 1970’s in Greek islands and Turkey before settling in Vancouver, B.C. in 1972. His wife taught and William found a niche market, finding woefully underpriced items at the Salvation Army and upselling them to specialty dealers.

Philly in the late 60’s was a city on fire, when it wasn’t a simmering pot ready to boil over. David had purchased a 12-room home in a rough neighborhood. It was there that he learned the most about living around fear, violence, murder—Philly was a war zone. They were burglarized, had their car stolen, and their windows shot out.

In 1967 David began dabbling in film while still a student at the Academy. He made a few shorts and by 1971 had moved with his wife and daughter to Los Angeles to study fim at the American Film Institute. It is here, ultimately, that “Eraserhead” was made. That movie, as weird as it was, got him Elephant Man, and that film was his entre’ to Hollywood and the film industry.

The seventies were a little harder on William as a writer. Discovering the racket of professional student, he rode that up through ‘77 before attaining a degree in English. It was there that he wrote his first short-story, “Fragments of a Holograph Rose”. It was published the same year in Unearth, a sci-fi magazine. He frequented sci-fi conventions and finally began getting noticed by a few other authors who encouraged him. His discovery of punk music in 1977 had re-awakened his 12 year-old’s desire to write, something that had been buried beneath parenthood and the grind of life. It was to be part of the connection he made with fellow authors Bruce Sterling, Rudy Rucker, John Shirley, and Lewis Shiner. At a sci-fi convention in Austin, TX in October of 1982, this group of authors did a panel on "Behind the Mirrorshades: A Look at Punk SF". Gibson dropped the novel Neuromancer in 1984. It took the Hugo, Nebula, and Philip K. Dick Awards.

Nobody had done that before.

In 1977, Eraserhead had made a strange splash in Hollywood. In 1980, The Elephant Man was released, directed by Lynch. It received eight Oscar nominations including one for best new director. In 1984, he directed Dune, and it failed in the box office. Moreover, Lynch lost control of the project and had to make compromises with his artistic vision. His next film, Blue Velvet, was released in 1986. The viewers had difficulty with the film, but did have modest financial success.

The critics loved it.

So here are both men, from the same era, having wildly different backgrounds, both having achieved success at about the same time. From here, Lynch will bring us on the arc of Twin Peaks, from nostalgia to narcissistic nihilism, spanning twenty-five broadcast years. His other films will dive into TM-fueled surrealism (Mulholland Drive, Lost Highways, Inland Empire) road trips like Wild at Heart (violent and sexual, rated R) or The Straight Story (rated G and so sweet it’ll make your teeth hurt).

William Gibson’s continued to write books that are futuristic in some regard. Not future like star travel as much as future like having the web access in your mind. In some respects time has nearly caught him. In the early 2000’s his books moved from hot niche to bestsellers, likely as much because his readers were fully into their thirties and older, looking for less sizzle and more substance. Perhaps William’s readers matured with him.

This brings me to a difficult conclusion. I have, at different times, loved both of these men’s works and soaked them up like cloud-tinged sunshine, blissful radiant heat tempered by chill air. They have personal stories that parallel and diverge wildly. They echo in one another, mirror, and also oppose. Balance. Perhaps William is the coffee, bitter and steaming, to David’s pie, warm from the oven and sweet. Quaint, but simplistic.

When I first began considering this as a topic, it seemed clear—Lynch is the nostalgic past to Gibson’s cynical future. On the surface, this rings true only if you take selected pieces of Lynch’s work—season one and two of Twin Peaks, Blue Velvet, and ignore his more modern-feeling and less nostalgic works. Simply seeing season three of Twin Peaks shows that David isn’t just trapped in nostalgia, opining for a more wholesome time, far from it. Even in the most sappy moments of Twin Peaks, a very real and timeless evil lurks. Over three seasons and twenty-five years we are shown a shift in balance. The coffee’s perc’d too long, the pie’s stale and tasteless.

In Gibson’s works, there’s always a hope of finding some way to navigate this increasingly complex world, to hang on to a thread of decency, or at least of humanity. That our way to win is simply to keep existing in our humanity.

To be fair, my view of Gibson’s writing is shaped by his six novels, commonly referred to as Sprawl Trilogy and Bridge Trilogy. Writing this has encouraged me to return to the well; his next three are on order. Blue Ant Trilogy, consisting of Pattern Recognition, Spook Country, and Zero History. They are set more or less in the time we no are in, or were when these books were written, post-2000 to 2010.

I’m looking forward to catching up with William Gibson, or his writing, anyway. I do wish that there were some sense of religion to his work; humans are by nature spiritual beings. As for David Lynch, I hope he will yet put something on film, and I hope it’s a little bit more like Twin Peaks than Inland Empire. As for religion, David’s Transcendental Meditation seems to inform much of his work, especially the stranger things. I would never wish aware the horrible strangeness coloring his films, only to see them rooted in and identified with the spiritual realm they truly come from.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got a percolator to clean.