May 16th my son, 12 years old, was confirmed in the Faith by Bishop Tissier de Mallerais. The bishop is a 78 year-old Frenchman, whip-thin and stooped from a life bent over books as well as bearing the weight of one quarter of the Society of Saint Pius X for most of the years since his elevation to bishop in 1988, now one third—there are three active bishops serving with over 700 priests. He has a wild way of talking when he preaches in English, his voice often hitting falsetto notes momentarily as his pitch makes wild roller coaster waves. It must be a French thing, perhaps an oratorical affectation more common to his generation or perhaps because he was preaching primarily to the children.

Bishop Tissier de Mallerais, SSPX

He proved to be most affable, setting nervous children and adults alike at ease as we greeted him by kneeling and kissing his ring. He asked me how long I’d been in my wheelchair (Old Sparky). I explained to him that it had been only a few months after beginning our attendance at the priory that I had had my stroke. He was quick to remind me of the need for sacrifice, and I reassured him that I trust God gives me what I need, which is my polite way of saying I know I needed a whoopin’ and being kicked squarely in the pride. Which I did get a double-serving of.

Coming to the priory in 2020, we’d reason to look for a new home for our Faith and souls. Some reasons came out of Covid, others I’d just as soon let lie like a sleeping dog. No reason now to go digging up those old bones.

We didn’t know anybody who went there, hadn’t had someone sell us on the Society. I had done some reading, studying.

Our first Mass was a low Mass on a weekday. The inside of the church was beautiful, the Mass mostly quiet; me knelt through nearly all. It was meditative.

We began regular attendance on Sundays and made Confessions there with the priests who seemed peaceful, solemn, and intent.

Maybe a month in, there was a little get-together out back of the reception hall in a large grassy area. There were burgers, hotdogs, all the normal fixin’s for a summer cookout. We finally did start meeting a few of the faithful that attended alongside us. And they weren’t all poster Trads like the internet would have you think. And they weren’t all tweed-jacket pipe-smokers. One or more of the fellas had swapped suit for shorts, a tank top and an open-carry sidearm. Bear in mind, it was a hot August day.

Father helped me sort out the business of my Church of Christ baptism, which was in a crawdad hole in a creek in the coastal mountain range. It went clear to a canon lawyer who, when he came back from Europe, talked with my priest about how odd those Church of Christ folk are about baptism among the protestants, in taking it serious the way a good Catholic priest would, meaning my baptism was valid. So Father supplied the prayers of exorcism from the old Rite which were lacking.

It was a beautiful evening.

Then came my stroke, and I was gone for six weeks. During Covid, in the hospital, my options were extremely tight. A Catholic hospital didn’t want me to see any priest but theirs. Father fought and pushed and wrangled, and got in to see me once, where he said a private Mass for me, heard my confession and gave me Holy Communion.

It was a beautiful day.

We had noticed that we were being watched by the lay-folk before my stroke. Not in meanness, glaring, or suspicious. Just waiting, I think, to see if we’d stay. To see if we were going to go crazy in one direction or the other. I was, after all, the only long-haired friend of Jesus in there; all I needed was a microbus. I’d always run into a small basket of odd ones at any parish I had attended, so you might say it was politely mutual.

I came home in November and we began putting our lives back together, bit by bit. Our life as a family attending Mass resumed, with a twist. Now I was a guy in a wheelchair, for one. For another, we weren’t sure how our finances would be. And the stresses of re-integrating me into the home were likely written all over our faces. We were stressed. My wife was carrying such a load.

It turns out that a Ferrari-red wheelchair can be a conversation-starter. We slowly began meeting more and more people. Most didn’t recognize me in the wheelchair, my face stroke-droopy to one side. One large family had us out to their place up on top of a knoll in the woods. We met a few others at the local eateries around town. One of the families had a huge forth of July bash out on their place, everyone who wanted could come.

We’ve been at the priory two years this fall. I don’t know if we’ll ever become a fixture there, but it sure feels like home. Mind you, some folks have a sort of “pioneer” status, having been attending since before the priory was ever built. I’m o.k. with that. It’s not like we’ve been ostracized as newbies.

Did I mention the nuns? We’re so blessed to have six sisters living a semi-cloistered life in a convent on the property. They take care of the priests, cooking and taking care of the altar linens. They teach catechism in the Academy school, which is going back to k-12 after several years of cutting back to k-8. They pray the Divine Office with the priests and they sing in the choir for High Masses. I’m tellin’ ya, bring a rope so you don’t float away like St. Joseph of Cupertino. It’s sublime.

Some of the Sisters in front of the beginnings of the Immaculata in St. Mary’s, KS, 2021

But above all, they pray for us, and for the priests. I loved them as soon as I saw them.

My title mentioned the traditional Catholic life. That’s bigger by far than assisting at a traditional Latin Mass. That’s the centerpiece, the font of graces our life is to revolve around, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and chapel life.

The Catholic life can be very full if one is a position to participate. We’re always invited to join various hours of prayer with the priests and nuns. The liturgical calendar is ripe and bursting at the seams with saints to celebrate and venerate. There are many old practices, devotions and prayers to revive. There are deeper matters in the family, in marriage, in finding the roles traditional to husband and wife and children. That takes a lot longer. You can put it on like a coat, and wear it around, that’s o.k., it takes some time for these things to become integral to who you are. Eventually, it’s not on you, but in you.

I see some younger families in Tradition, and I’m tempted to wish I’d got started earlier. I could have made different decisions at a time when they were still possible; when I still had the youth, and health, and vigor to do so. Maybe I would have been able to realize my dream of building a life in the country on a little patch of land; of being poor but happy with my feet in the mud and hands on animals every day, and every day spent out in the world God made and gave to us, surrounded by a loving wife and a mess of kids.

The “if only” game is easy to play, for some a mere moment’s wistful distraction, but for most it is a path that only ends in anger, sadness, disillusion, ingratitude. Indulge me this, and I’ll be as brief as I can. You know I had a stroke. What you don’t is that I had several transient ischemic attacks-TIA’s-and didn’t go to the doctor. Instead we did what we could at home. When I had my second-last attack I was still roughly 200 miles from home. I drove my semi all the way home. I could have gone to a hospital at any time. For “reasons”, as the kids say, I didn’t. As a direct result I am hemiplegic, likely for life. My choices, consciously made. The last attack caused permanent brain injury. A small part of my hard-drive died. I rolled dem bones and got snake-eyes.

Or did I?

I had a commercial driver’s license, regulated by the federal government. For the greater good of the motoring public, my license to operate commercial vehicles was suspended for a minimum of two years whether or not I made a full recovery. If I had made a full recovery there would have been no help for me, a high school grad with a couple years of college and six years of military, a guy in his 50’s who had lost his only big marketable skill.

We would have lost everything by the time those two years were up. As it is, we got what we needed. I’m home, never to go out the door to a job again, with a chance to spend some time with my son before he’s grown and gone. And my wife needed me home in the worst way. We aren’t drowning in money, but it has been enough. And I’m learning some much needed lessons and cultivating woefully absent virtues because of all this.

So the “what if” or “if only” game is seductive, harmlessly fun if you keep it on the surface and don’t internalize the larger message that you’ve been cosmically ripped off. Your job is to figure out what you are supposed to be gaining from your hardship, suffering, or what you’re supposed to be letting go of.

How does this relate to living the traditional Catholic life? It’s not the sole possession of traditional Catholicism, but I have found so much wisdom, such embrace of the traditional theology of suffering not just in the clergy but in the joe sixpacks in the pews. You can’t give birth to fourteen babies and work to provide for them all willingly without embracing and plumbing the depths of suffering and its value for us. On the flip-side, to be amongst people who embrace large families so willingly and to be barren is to feel the sting of that poverty so much more sharply.

Catholics in general contracept like everyone else, although they aren’t supposed to, so being in a diocesan parish where the big families (few and far between) might have four children or even five and the norm is one or two, it’s easy not to feel the sting. It’s easy to hide. They follow the culture’s path to success—go to college, get established in a career, then get married. By that time, unless a thirty-five or forty year-old guy is marrying a woman just out of high school, the woman’s biological clock is on fire. The quality of her eggs is low, and conception becomes problematic. If she’s spent the last fifteen or twenty years playing with her body using hormonal contraception, it takes time after getting off them for her body to restore the hormonal balance necessary to be fertile. For many, there is just not enough time.

We’ve been there in those larger parishes out in the diocese. I don’t miss it.

So, let’s have fun with some stereotypes and distortions of traditional Catholic families and chapels.

They are joyless people, mean-spirited legalists.

The truth is, at Mass people may look more intense or serious at Mass. This does not mean they are joyless. It is simply that traditional Catholics tend to be very focused and intent during Mass. Outside of Mass they are still human, with a wide array of senses of humor and a sense of playfulness—once they get to know you. It takes time and patience on your part. As far as religious observances, they’re there to sanctify their souls. Remember that they are observing what had been standard practice prior to the 1960s, just plain old Catholicism that is now considered excessively rigorist by many outside the Latin Mass communities. “Our little experiment” is simply keeping these things rather than discarding them. Give it time and an open mind. Nobody was put in the stocks in the parking lot for not perfectly observing Rogation Days.

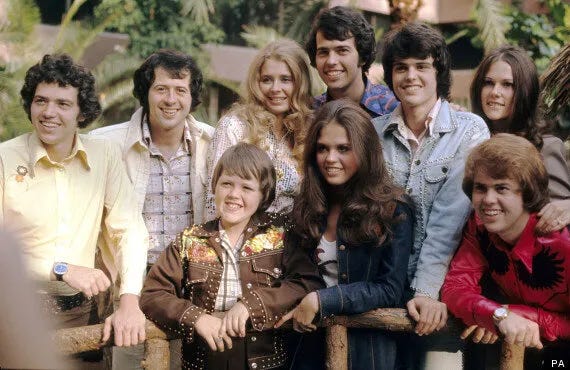

They all have Osmond-sized families.

My family of three blows the curve, sorry. I’m a stat-buster. People come to tradition at various stages of life; some earlier, some like me, much later. Also, traditional Catholics are not immune to fertility issues. Bottom line, God’s in charge. As people get to know one another, over time, stories are shared. Nobody threw rocks at us, anyway. However, there are a lot of full-size vans in the parking lots and a few families that fill a pew and might even need overflow.

They all look like Amish Catholics, or like they are auditioning for “Little House on the Prairie”.

To be fair, some do. Some don’t. My wife finds it difficult to find dresses and modest clothing that are fashionable, coming from Canada’s fashion and financial hub. Men’s clothing is so much easier. Most guys (not all, I didn’t and still don’t) have a suit, or at least a sports jacket. But if you wanna do the Chesterton thing, or Charles Ingalls, or release your inner Pennsilfaanisch Deitsch, any era that has a little more formal style—have at it brother, far as I’m concerned. Just don’t go full-on steampunk, that could be distracting. Our culture doesn’t have much to draw on. It might be a place where a little indulgence is fine, steal good fashion ideas from different eras if you want. I’m going to see if I can source some dresses for my wife from the Trad Wives of Twitter.

They’re all dirt-poor/well off.

Hard to say. Honestly, our priory has a little bit of everyone, I suppose it depends on where you live. Priories and chapels do inspire long commutes and relocations, so not everyone who attends there is from there, or is economically dependent on the local economy.

They are ethnically monochrome.

Same as above. The people attending reflect the greater population of the region.

The young men all look like stand-ins for Chesterton, or steam-punk lite, or cast members of a Dickens’ movie.

Every place will have it’s own vibe, that’s the best I can tell you. It’s not true where I go.

They’re all Distributists and live like it.

No, that’s the internet for ya. There are traditional folks who like distributism and who share a zeal for “back to the land” movements as well as family businesses of all kinds, but it is by no means a majority. I’d be surprised if more than a big handful of people at Mass knew much all about distributism.

The priests are strange compared to diocesan priests.

My experience with Society priests is small time-wise; however, attending a priory means that I have contact with all of the priests that serve a large area; ours covers parts of multiple states, and as bishops close down more Latin masses the requests keep coming. We have four priests working out of the priory, plus two others were there and have moved to other assignments. If I were at a chapel I might only see the same priest once a week or even once a month. So far I find them to be refreshingly down-to-earth, level-headed, masculine, and they don’t hang out with the laity in a way that blurs lines. It reminds me, in a good way, of my time in the military. There is a level of familiarity between officers and enlisted that work together, but also a certain healthy distance. I’d like to add, with priests living in community, and with the support of the Sisters, this lends so much stability of life. It is a well thought-out way of life for them to live, and we benefit.

The kids are all maladjusted weirdo homeschooled freaks.

I find the children delightful, which is good, because there are a lot of them and more on the way. Many of the children attend the priory’s Academy. We are blessed to be able to have it. I do not think this is the norm. Through the generosity of benefactors who were able to foot the bill for the building of most of what is here—convent, Academy, as well as a beautiful Church, there are things here that you won’t find at most other small chapels. That makes my experience somewhat of an outlier in some respects. We are homeschooling, as we live a little too far to run back and forth twice a day on our limited income, it would hasten the demise of our car and run our gas bill way up. I think I might look into the distance Catechism classes for my son, though. But the kids are great, eight year old girls carting around little brothers on the hip are the norm. Or teen boys, for that matter, caring for young’uns. It’s sweet to see.

You will be greeted at the door by the dress-code Gestapo.

The vast majority of folks drawn to Society chapels, and to the traditional Mass, seem to already know a little of etiquette. I haven’t seen anyone get a drill-instructor shark attack for not veiling or wearing something deemed inappropriate. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen in some places, and it breaks my heart.

They are an extremely insular, tight-knit community with lots of intermarriage, they’re all related and grew up together and have known each other for generations.

Well, o.k.. There can be some truth to this, as traditional families will move long distances to be at a chapel or priory, and when you get siblings and relations and kind of mass immigration of an entire branch of a family tree, sure. Add to this that a chapel or priory may be in a smaller town, you get small-town life. So you may or may not find elements of this, it varies. We have a core of folks who share different levels of kinship, a layer of people that are local to the area and have known each other a long time, and also a large number of converts like me. It’s a healthy mix.

It’s all old people who couldn’t handle all the changes of the 1960’s and 1970’s in the Church and society.

Ummm, NO. I’m thinking of the age of people attending, you have to be at least 60 years old to remember the Old Mass and how things were, and I’d say 70-80 years old to have formed the kind of deep attachment through memory and experience-based nostalgia our detractors claim we have. I doubt you will encounter a Latin Mass community that looks like an old folks home anywhere outside of one. The 70+ age bracket in our community is moderately small. Definitely not the dominant demographic, that’s more likely your 30-50 group.

So that’s what have for you, I hope it wasn’t too “inside baseball” for you. Feel free to ask questions, I’ll do what I reasonably can to answer.

It’s a good life.